Like a Kindling Fire: |

|

| Edward C. Sellner, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of Pastoral Theology and Spirituality at the College of St. Catherine, St. Paul, MN. He is the author of Mentoring: The Ministry of Spiritual Kinship (Ave Maria Press, 1990), and Soul-Making: The Telling of a Spiritual Journey (Twenty-Third Publications, 1991). |

Drawing on the image of fire, Augustine associates friendship and fire, describing friendship as a sharing of the counsels of the heart.

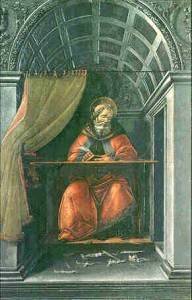

AT the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy, there is a painting by Botticelli entitled "St. Augustine in His Study" that shows the early church father with gray and thinning hair writing in some sort of book or journal with a white-feathered pen. At his feet are tattered sheets of paper, possibly from a composition that he had written and discarded. What is striking about the portrait is that Augustine is alone, which -- judging from what we know of his life -- was surely a rare occurrence. Besides the pastoral duties and administrative responsibilities which took up so much of his time as priest and bishop (the latter of which he frequently complains in his letters)(1), there is the simple fact that Augustine hardly ever spent a moment of his life without some friend close by. Even his dramatic conversion at the age of thirty-three in a Milanese garden took place in the presence of his friend, Alypius, who is practically holding the book that Augustine takes up to read. When Alypius himself, following the example of his former teacher, is immediately converted, the two of them rush to Augustine's mother who is evidently not all that far away (Confessions, VIII, 182-183). This is surely one of the predominant patterns in Augustine's life: the constant presence of friends, and his obvious appreciation of them. It contributed to his becoming one of the great pioneers of Western monasticism who, according to Brian Patrick McGuire, "took the lead in forging attitudes towards friendship" which influenced Western culture and theology (41). It is why Peter Brown can state that "no thinker in the Early Church was so preoccupied with the nature of human relationships" (32).

In this article I will examine the intimate relationships which influenced Augustine's understanding of friendship. My primary source will be The Confessions which contains Augustine's clearest statement on friendship. As we shall see, Augustine

closely identified those relationships and the interpretations of friendship which emerged from them with the imagery of fire.

THE WOMAN AUGUSTINE LOVED, THE MOTHER OF HIS CHILD

From his youth, Augustine was filled with the longing for union and the yearning for wisdom. Writing in The Confessions at the age of forty-three (ten years after his dramatic conversion to Christianity), he describes his adolescence and the natural

growth of puberty in the worst possible light. In Book II, he tells his readers that "in the sixteenth year of my flesh ... the madness of lust ... held complete sway over me," and introduces that period of time with the imagery of fire: "For in that youth of mine I was on fire to take my fill of hell." He goes on to associate that fire with a quality, though disparaged, that stayed with him throughout his life. "And what was it that delighted me?" he asks, and immediately answers: "Only this - to love and be loved." He then links the fire imagery with the love of friendship. "But I could not keep that true measure of love, from one mind to another mind, which marks the bright and glad area of friendship" (Confessions, II, 40-42).

In Book III Augustine uses the same imagery and makes the same connection. At the age of eighteen, he says, "I came to Carthage, and all around me in my ears were the sizzling and frying of unholy loves. I was not yet in love, but I loved the idea of love .... It was a sweet thing to be loved, and more sweet still when I was able to enjoy the body of my lover." The very next sentence, after his reference to the body of his lover, is telling: "And so I muddied the clear spring of friendship with the dirt of physical desire and clouded over its brightness with the dark hell of lust" (Confessions, III, 52). This sexual relationship with a woman who remains unnamed throughout his Confessions lasted for thirteen years, from 372 to 385 C.E.. From their union came a beloved son, Adeodatus, born in 373, who emerges in Augustine's autobiography, The Teacher, as an exceptionally precocious child and close friend (Colleran 115-186). Although Augustine equates his relationship with his concubine with an inability to control his sexual desires, it is clear from the short description of its termination how much the two of them loved each other: "My heart, which clung to her, was broken and wounded and dropping blood. She had returned to Africa after having made a vow to you [God] that she would never go to bed with another man... " (Confessions, VI, 132-133). It is also clear that although the classical culture which had shaped Augustine believed that only men could be friends (since friendship presupposed the full equality of those involved, and only men had that), Augustine applied the term friend to his female lover and the mother of his child.

CICERO AS FRIENDLY MENTOR

The imagery of fire appears again shortly after Augustine's move to Carthage. His father had died when he was seventeen, and now at the age of nineteen and a student of rhetoric, he discovers Cicero's Hortensius. As a result of reading this book, he tells us, "my spirit was filled with an extraordinary and burning desire for the immortality of wisdom .... I was on fire then, my God, I was on fire to leave earthly things behind and fly back to you, nor did I know what you would do with me; for with you is wisdom. But that book inflamed me with the love of wisdom (which is called philosophy in Greek)." This discovery of Cicero's writings had a significant effect on the course of Augustine's life; it was in fact a turning-point in which his heart was changed profoundly: "I was urged on and inflamed with a passionate zeal to love and seek and obtain and embrace and hold fast wisdom itself, whatever it might be" (Confessions, III, 56-57). Although another twelve years would pass before his Christian conversion, the mentoring Augustine received from Cicero had a lasting effect on his life and thought, not only regarding his passionate quest for wisdom, but in his understanding of the meaning of friendship.

In De Amicitia (or Laelius: On Friendship), written around 44 B.C.E., Cicero describes a friend as an alter ego or another self, and succinctly defines friendship as "complete identity of feeling about all things in heaven and earth: an identity which is strengthened by mutual goodwill and affection." He states that "with the single exception of wisdom" friendship is "the greatest of all the gifts from the gods," and "the finest thing in all the world." It is a source of profound happiness, and, he writes, "the significance of friendship is that it unites human hearts." Cicero's book on friendship takes the form of a dialogue whose main character is Gaius Laelius Sapiens, and the occasion for this famous orator's reflections is the death of Scipio Africanus, his close friend. Cicero has Laelius saying at one point:

Without affection and kindly feeling life can hold no joys. Scipio was suddenly snatched away .... We shared the same house, we ate the same meals, and we ate them side by side. Together we were soldiers, together we travelled, and together we went for our country holidays. Every minute of our spare time ... we devoted to study and research, withdrawn from the eyes of the world but enjoying the company of one another.(2)

As we shall see, Augustine uses similar language in The Confessions describing his own friend who dies suddenly, as well as the sort of activities with other friends that helped assuage his extreme grief at that loss. The influence of Cicero, who lived over four hundred years before Augustine, reveals how friendship is not limited to contemporaries. Along with Plato, Plotinus, and Porphyry (Brown 88-100), Cicero was a significant teacher and spiritual mentor for Augustine. He obviously admired the great Roman statesman and orator, and wrote on the same subjects as Cicero, such as friendship and the happy life, (3) using the same dialogic approach. He also quotes Cicero's definition of friendship in an undated letter to Marcianus, whom he describes as "my oldest friend" whom he hopes will join him in baptism, so that their friendship finally will be as all true friendships are, united in Christ (Baxter 491-9). Writing at the age of seventy, he echoes his mentor's words about the profound happiness and support associated with human friendship: "There is no greater consolation than the unfeigned loyalty and mutual love of ... true friends" (City of God, 447).

THE FRIEND WITH WHOM "MY SOUL COULD NOT DO WITHOUT"

Book IV of the Confessions contains Augustine's fullest explanation of what friendship is and, by implication, what it is not. Again he uses a story from his life to explain his theology and, once again, he begins this section of his autobiography with reference to those desires which he had earlier equated with fire: "So for the space of nine years (from my nineteenth to my twenty-eighth year) I lived a life in which I was seduced and seducing, deceived and deceiving, the prey of various desires" (Confessions, IV, 69-73). (Evidently now, since he has settled down with his friend and lover, the cravings are more intellectual than physical.) We find him, at the beginning of manhood, living with his concubine and young son, teaching rhetoric, attracted to astrology and the "vanity of the stage." In 375, he moves to Tagaste, his birthplace, to continue teaching. It is there that he introduces to the reader a close friend from childhood: "We were both of the same age ... ; he had grown up with me as a child and we had gone to school together and played together." This friendship, he says, "was sweeter to me than all the sweetness that in this life I had ever known." In some ways, their relationship today might be associated with youthful infatuation or even co-dependency, for as Augustine himself acknowledges, "my soul could not be without him," and "we depended too much on each other." He goes on to state (from the hindsight of his Christian conversion and his own developing theology) that the other was "not ... a friend in the true meaning of friendship." Here in Book IV, chapter 4, Augustine most clearly defines what friendship from his perspective means: "there can be no true friendship unless those who cling to each other are welded together by you [God] in that love which is spread throughout our hearts by the holy spirit which is given to us" (Confessions, IV, 73).

Despite this later interpretation, at the time this friendship was highly valued by Augustine, one that "had ripened in the enthusiasm of the studies which we had pursued together." He identifies it with much happiness, and he was obviously devastated when his friend suddenly contacts a high fever, is baptized, enjoys a brief remission from his illness, and then dies. It was a tremendous blow, evidenced in the way he describes this personal loss:

My heart was darkened over with sorrow, and whatever I looked at was death. My own country was a torment to me, my own home was a strange unhappiness. All those things which we had done and said together became, now that he was gone, sheer torture to me. My eyes looked for him everywhere and could not find him. And as to the places where we used to meet I hated all of them for not containing him .... (Confessions, IV, 74-75)

Like the stories of the young Buddha on the road who encounters an elderly man, and Gilgamesh at the death of his friend, Enkidu,(4) the loss of Augustine's friend confronts him with his own mortality. Beside himself with grief, "I became to my self a riddle," he says: a person "tired of living and extremely frightened of dying." He found only tears, tears that "had taken the place of my friend in my heart's love .... I was in misery and had lost my joy." And he adds, quoting the classical writer, Horace:

I agree with the poet who called his friend "the half of his own soul." For I felt that my soul and my friend's had been one soul in two bodies, and that was why I had a horror of living, because I did not want to live as a half being, and perhaps too that was why I feared to die, because I did not want him, whom I had loved so much, to die wholly and completely. (Confessions IV, 75-77)

OTHER FRIENDS IN CARTHAGE, ROME, AND MILAN

In an attempt to escape his extreme unhappiness, Augustine returned to Carthage in 376, knowing full well that the pain would go with him, "for my heart could not flee away from my heart, nor could I escape from myself." There we find him once more returning to the imagery of fire -- associating it now not exclusively with sexual longings nor intellectual pursuits, but with the ties of friendship. The comfort he found in these other friendships in Carthage, Augustine says, "helped most to cure me" of his grief. Echoing the words of Cicero, he describes many of the joys of friendship:

... to talk and laugh and do kindnesses to each other; to read pleasant books together; to make jokes together and then talk seriously together; ... to be sometimes teaching and sometimes learning .... These and other similar expressions of feeling, which proceed from the hearts of those who love and are loved in return, and are revealed in the face, the voice, the eyes, and in a thousand charming ways, were like a kindling fire to melt our souls together and out of many to make us one. (Confessions IV, 77-78).

In this company of friends, Augustine continued his teaching, wrote two or three books on the topic of beauty, and, according to Book V of The Confessions, became a follower of Manes and Faustus. Moving eventually to Rome (in an attempt to flee unruly students), and then settling in Milan, he met, as we know, Ambrose, someone who "welcomed me as a father." To this important mentor, Augustine opened his heart: "I began to love him at first not as a teacher of the truth (for I had quite despaired of finding it in your church), but simply as a man who was kind and generous to me" (Confessions V, 108).

ALYPIUS AND NEBRIDIUS

In Book VI, with Ambrose's preaching, and, most of all, lived example of Christian life, as well as Monica's re-entry into his own, Augustine's conversion process intensifies, helped on by those whom he refers to as his "intimate friends" (Confessions VI, 120). Two of them in particular, Alypius and Nebridius, were and remained life-long friends. Alypius had been born in the same town as Augustine, was younger than he was, and a former student of his in Carthage. Despite the differences of age and education, mutuality was a key dynamic of their relationship: "He was very fond of me, because he thought me good and learned, and I was very fond of him because of his natural tendency toward virtue which was really remarkable in one so young" (Confessions VI, 121). They shared a love of learning, and, according to Augustine, "together with me he was in a state of mental confusion as to what way of life we should take" (Confessions VI, 126-127). They were eventually baptized together, lived a monastic life-style at Tagaste from 391-394, and some months before Augustine became a bishop at Hippo, Alypius was consecrated bishop of Tagaste where he remained until his death about 430 C.E. Years after his conversion, Augustine describes Alypius quite simply as "the brother of my heart," and in a letter to Jerome, written in 394 or 395, he states that "anyone who knows us both would say that he [Alypius] and I are distinct individuals in body only, not in mind; I mean in our harmoniousness and trusty friendship" (Baxter 57).

The imagery of fire returns to Augustine's Confessions when he tells his readers about the other close friend, Nebridius, whom he had first introduced in Book IV, just before describing the loss of his other unnamed friend. He referred to Nebridius then as "a dear friend," and "a really good and a really pure young man, who used to laugh at the whole business of divination" which Augustine was pursuing at the time (Confessions IV, 73). This wealthy young man had left his family estate near Carthage and journeyed to Milan in order, Augustine says, to "live with me in a most ardent search for truth and wisdom. Together with me he sighed and together with me he wavered. How he burned to discover the happy life! How keen and close was his scrutiny of the most difficult questions!" And so, he continues, "there were together the mouths of three hungry people, sighing out their wants one to another" (Confessions VI 127). Others made plans to join them in a communal life in which all possessions would be shared, but the plans were abandoned as impractical, primarily due to the objections of the wives to whom some were married. The idea remained, and, along with Augustine's communal lifestyle with friends before and after his conversion, contributed to his writing in 397 C.E the oldest monastic rule in western Christianity. This rule proposed an ideal of monastic friendships that would be expressed in sharing of all property, living together in harmony and being "of one mind and one heart" (Rule 11).

Alypius and Nebridius continued as intimates of Augustine in that process that he refers to in Book VIII as God's "setting me in front of myself, forcing me to look into my own face" (Confessions, VIII, 173). As we know, Alypius was with Augustine in the garden, heard his anguish and tears, and was present when "it was as though my heart was filled with a light of confidence and all the shadows of my doubt were swept away" (Confessions, VIII, 183). The two of them, together with his son, Adeodatus, were later baptized by Ambrose -- with Monica looking on. As Augustine describes the scene, alluding to his own great appreciation of music and liturgy:

And we were baptized .... What tears I shed in your hymns and canticles! How deeply was I moved by the voices of your sweet singing Church. Those voices flowed into my ears and the truth was distilled into my heart, which overflowed with my passionate devotion. Tears ran from my eyes and happy I was in those tears. (Confessions, IX, 193-194)

Augustine returned to Nebridius in Book IX of The Confessions: "Not long after our conversion and regeneration by your baptism, you [God] took him from this fleshly life; by then he too was a baptized Christian. . His great love and affection for this friend is clear, as is his belief that friendship in Christ survives even the yawning chasm of separation death brings. In words that Dante will use in his Divine Comedy to refer to God, and C.S. Lewis will, draw upon in his grief at the loss of his wife, Joy Davidman,(5) Augustine says this about his dear friend, especially remembered for his questioning mind:

And now he lives in the bosom of Abraham.... There he lives in a place about which he used often to ask questions of me, an ignorant weak man. Now he no longer turns his ear to my lips; he turns his own spiritual lips to your fountain and drinks his fill of all the wisdom that he can desire, happy without end. And I don't think that he is so inebriated with that wisdom as to forget me; since it is of you, Lord, that he drinks, and you are mindful of us. (Confessions, IX, 187-188)

AUGUSTINE'S UNDERSTANDING OF FRIENDSHIP

With the conversion and baptism of Augustine and his eulogy to Nebridius, we have come full circle: from the sudden loss of his first friend with whom his soul was intertwined to that of the vision of his Christian friend drinking his fill of wisdom; from tears of anguish at his young friend's death to tears of happiness at his own and his friend's baptismal regeneration; from fear of dying when he had first encountered his own mortality to the Christian faith that our friendships live on in a God who is always mindful of us; from the search for love and wisdom in many pursuits to centering his life in Christ. Augustine went on to become a priest and bishop, to start a monastery and write a rule, but it is only because of these early friendships, remembered in that ""great harbor of memory" (Confessions, X, 218) in the depth of his soul that he was able to write so insightfully about human friendships and the friendship of God.

What is true friendship, according to Augustine? Nothing else but the welding together of two souls who seek the same goal; nothing more than two hearts united by the holy spirit who is God. This is the understanding that emerges in Augustine's Confessions and other writings, including his letters. It is similar to that of Plato, Cicero, Plotinus, Horace, and classical writers who rated friendship and dialogue with friends as the highest calling of humankind. It is a pattern that Plato in his Symposium describes as that of being drawn, with the help of one's friends, from desire for a beautiful body to love of wisdom to immortality (233-286). That pattern in Augustine's youthful years is discernible in his Confessions, and one that he quite possibly consciously used to portray his own journey to Christian faith. But for him as a Christian theologian, there is one important difference between Platonic concepts and his own. While friendship by classical writers is described as a search together for beauty, truth, and wisdom, in Christian friendship, the search ultimately leads friends to the source who is Beauty, Wisdom, Truth, and Love. This personal God of the Christians, Augustine writes in one of his letters in which he quotes a line from Scripture that the medieval Cistercian Aelred of Rievaulx will take up and make his own, is a God of love, "and he who abides in love abides in God."(6) We see traces of this love -- in all its wandering, pilgrim ways -- in the life of Augustine and in those friendships, which, he says, "like a kindling fire melted our souls together and out of many made us one."

But what is the source of Augustine's own great passion to love and be loved, his yearning for truth and wisdom, his all-embracing desire for union with God? How does God work to lead him (as Augustine believed God does in all Christian conversions) to his true self? What accounts for Augustine's obvious ability to form such intimate friendships and find such joy in them? Here, I believe, we must turn to the one relationship only hinted at thus far, that of his mother, Monica.

MONICA

Peter Brown says that Augustine's "inner life is dominated by one figure -- his mother" (29) and, according to Augustine's own story, she is with him at many crucial turning-points. He first makes reference to her in Book I when he says that as a newborn he "was welcomed ... with the comfort of woman's milk." In Book II, he tells us that when he was entering adolescence Monica privately warned him "not to commit fornication and especially not to commit adultery with another man's wife." In Book III, she has a dream in which "a very beautiful young man with a happy face" assures her that her son will later be converted, telling her that "Where you are, he is too." In Book V, her bitter tears for Augustine "daily ... watered the ground" when he plans to sail to Rome. In Book VI, she joins him in Milan, and plays, he says, "a large part" in getting rid of his concubine so that he can be properly married. In Book VIII, she hears of his and Alypius' conversion, and in Book IX she dies at the age of fifty-six (Confessions I, 6; II, 3; III, 66-67; V, 101; VI, 131). Augustine describes her death, however, only after he summarizes her life and one of their last meetings.

There at the coastal town of Ostia, located on the banks of the Tiber River, he returns to the imagery of fire and, significantly, the symbol of the eternal fountain which he had mentioned earlier in his eulogy to Nebridius:

So we were alone and talking together and very sweet our talk was ... discussing between ourselves and in the presence of Truth ... what the eternal life of the saints could be like.... Yet with the mouth of our heart we panted for the heavenly streams of your fountain, the fountain of life. Then with our affections burning still more strongly toward the Selfsame, we raised ourselves higher and step by step passed over all material things .... [We] came to our own souls, and we went beyond our souls .... And, as we talked, yearning toward this Wisdom, we did, with the whole strength of our hearts' impulse, just lightly come into touch with her, and we sighed, and we left bound there the first fruits of the Spirit, and we returned to the sounds made by our mouths.... (Confessions, X, 200-201)

Here, in this one scene, Augustine most clearly paints for us the meaning and direction of Christian friendship: two souls, two hearts united as one in the vision of eternal Wisdom. In this picture we also find a paradigm of the communion of saints: spiritual friends, transcending the ages, helping each other discover God's infinite love. It is no wonder that after this encounter and a life-time of memories Augustine says at the death of his mother: "My soul was wounded and my life was, as it were, torn apart, since it had been a life made up of hers and mine together" (Confessions, X, 205). Monica surely was, as Henry Chadwick believes, Augustine's "supreme friend" (69).

In Augustine's friendship with Monica, we find not only the source of his adult religious convictions (what Peter Brown calls "the religion woven into our very bones as children" [105]), but the origins of his own great capacity for intimate friendships with both women and men. Judging from references in his Confessions to his father, Patricius, Augustine had little regard or affection for the man (at least, not until after both his father's and mother's deaths). As a result, Augustine searched throughout his life for father-substitutes in his many masculine mentors. Besides Ambrose, there was Augustine's wealthy patron, Romanianus, who sponsored his early education, and remained a friend for life. For nine years, the Manichaean bishop, Faustus, served as a kind of "long-distance" mentor until Augustine actually met the man and was disillusioned by his apparent ignorance. Simplicianus, originally a mentor of Ambrose, became an important guide for Augustine, especially when he told Augustine in 386 C.E. the story of another man's conversion: "When [he] told me all this about Victorinus, I was on fire to be like him, and this, of course, was why he had told me the story" (Confessions, VIII, 167). Even the wisdom figures Augustine read, such as Plato and Cicero, or those he heard about, such as the desert solitaire, St. Antony of Egypt, acted in that mentoring capacity.

Despite the relationship with his father, or perhaps precisely because of it, Augustine was exceptionally close to his mother, and she to him: "She loved having me with her, as all mothers do, only she much more than most" (Confessions, V, 102). The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung calls this a "mother-complex," and though it can be associated with psychological illness, in its wider connotations it can have very positive effects:

Thus a man with a mother-complex may have a finely differentiated Eros.... Thus give him a great capacity for friendship, which often creates ties of astonishing tenderness between men and may even rescue friendship between the sexes from the limbo of the impossible. He may have good taste and an aesthetic sense which are fostered by the presence of a feminine streak. Then he may be supremely gifted as a teacher because of his almost feminine insight and tact. He is likely to have a feeling for history, and to be conservative in the best sense and cherish the values of the past. Often he is endowed with a wealth of religious feelings, which help to bring the ecclesia spiritualis into reality, and a spiritual receptivity which makes him responsive to revelation. (86-87)

All these attributes can be discerned in the writings and lifework of Augustine, and, with this interpretation of Jung we may, finally, have been given a clue to the meaning of the imagery of fire that is so prevalent in Augustine's Confessions.

For, according to Jung fire is a symbol of transformation and of eros, that powerful yearning within humankind for wholeness, freedom, wisdom. This "fire" is a spiritual force, a passion or enthusiasm for what and whom we love deeply that ultimately leads us beyond ourselves as well as to the deeper Self that lies within. While Augustine intellectually could and did acknowledge the spiritual side of that "flame," it is precisely the bodily aspect of eros which caused him so much anguish, personally and theologically. Personally, he struggled with a passionate nature that had difficultly in accepting limitations of any kind -- whether sexual longings or limits on work. Theologically, he was influenced by the Neo-Platonists who, though acknowledging Eros's importance to the spiritual quest, ultimately distrusted it and one's affective side in favor of reason. Augustine shared this belief, immersed as he was in that philosophical tradition and classical culture. He describes in the City of God how Socrates believed that "only ... a mind purified from passion" could comprehend "the origin of all things," including "the will of the single and supreme Divinity." As a result, Augustine failed to fully appreciate the goodness of passion itself, denigrating and condemning not only his own sexuality, but almost every form of sexual expression (146 ff.). Modern writers would disagree with him in that regard. C.S. Lewis points out in The Four Loves that the so-called "highest" loves cannot stand without the "lowest." Jungian psychologists would advise Augustine that all human relationships, including our friendships, have a bodily and sexual aspect to them, and that if there is no emotion, no affect or attraction between people, there will be no depth of intimacy either. Rosemary Haughton, among other contemporary theologians, would speak to him of how the incarnation makes holy all materiality and, bodiliness, and how sexual passion can lead us to greater maturity and self-giving. The mythologist Joseph Campbell would warn Augustine, as he would us all: "Be careful lest in casting out the devils you cast out the best thing that is in you." Even Socrates's mentor, the priestess Diotima, believed that Eros is a great demon which can act as a mediator between the human and divine. (7) If Augustine had perhaps taken that message in Plato's Symposium more seriously, and listened more closely to his feminine side, he might have been a little more trusting of his own eros and appreciated it more genuinely as a vehicle leading him to wisdom, holiness, friendship, and God.

From these perspectives, we can now see that references to fire in Augustine's writings are in fact references to Augustine's eros, and that, despite his own denigration of that passion as it is expressed sexually, eros -- in all its manifestations -- made him the person he was and the saint he was to become. Truly, his life (to use the poetic language of T.S. Eliot in "Little Gidding") was "tongued with fire" (139), and the directions it.took and the important relationships he made were touched by that fire: the fire of eros, the fire of friendship, the fire of God. Yes, eros, like fire, can have a destructive side; but it is also where the Holy Spirit works. This spiritual presence, as Augustine knew from his own experience, manifests itself in numerous ways, from the voice of a child in a garden to a kindling fire whose warmth and power unites human hearts. That spiritual power, in fact, most often seems to be manifest in the heart, and it is intriguing to note that whenever Augustine in his Confessions uses the imagery of fire, the image of the heart is in close proximity. That is where Augustine finally locates friendship, for, according to him, friendship is simply sharing the counsels of the heart.

This article, then, is about Augustine's own erotic passage to ultimate Wisdom, and how, through his many friendships, he was led to the God who unites souls and hearts. As his life story clearly shows, it is true that a person can be known by the friendships that he or she makes, or, perhaps, more accurately, that he or she is given. Monica was a significant part of that process; she did what Augustine in his writings considered one of the chief duties of friends: that of drawing each other closer to God. Because of her love, prayers, and persistence, the dream of her son's conversion had come true.

CONCLUSION

In one of Augustine's numerous letters that still exists, we find him writing to a friend:

When you have read this letter, use it as an invisible bridge to cross over and proceed in thought into my heart, and see what goes on there concerning you. There will be laid open to the eye of love the inner chamber of love, which we close against the troublesome trifles of the world when we adore the Lord. There you will see the ecstasy of my joy in that good deed of yours, which I cannot utter in my speech nor express with my pen, burning and glowing as it is in the sacrifice of praise of Him by whose help you carried it out. Thanks be to God for his unspeakable gifts. (Ep. 58,2, in Fiske 2-5)

If love is a shared vision and the heart a resting-place, a dwelling-place for our friends, as Augustine writes, then we can perhaps conclude that the original interpretation of the painting by Botticelli of an aging Augustine seated at his desk in the winter of his years was somewhat misleading. For even in Augustine's rare moments of solitude, he was really not alone. He was probably thinking of his friends, developing even greater intimacy with them in his memory and in his heart. Knowing what we know of him, we can imagine Augustine stopping his writing for a moment, putting down his pen, and praying for them to the God who had been revealed in his life as a God of friendship and a God of fire.

1. See J.H. Baxter, trans., St. Augustine: Select Letters (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980) where there are numerous references to the burden of his duties as a bishop as well as to his poor health. In 410, for example, he addresses a letter to his "dearly beloved brethren, the clergy, and all the laity," written from the count in which he laments that "in the weak state of my health I cannot adequately cope with all the attentions required from me by the members of Christ, whom love and fear of Him compel me to serve" (213).

2. See in this order of quotations Michael Grant, trans., Cicero: On the Good Life (New York: Penguin Books, 1984), 187-188, 227, 218, 221, 226-227.

3. See Grant, 49-116 for Cicero's The Tusculans on the essentials for a happy life. Augustine wrote De Beata Vita the same year as his conversion in Milan and retreat at Cassiciacum.

4. See "The Buddha" by Michael Carrithers in Keith Thomas, ed., Founders of Faith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986) and N. K. Sandars, trans., The Epic of Gilgamesh (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1972).

5. See Kenneth Mackenzie, trans., Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy (London: The Folio Society, 1979). In "Paradiso" Canto 32 (452-453), Dante refers to Beatrice, his guide who has brought him to heaven and her turning from him to God:

C.S. Lewis uses the same phrase (in Italian) at the conclusion of his book A Grief Observed (New York: Seabury Press, 1973), p. 60, when he describes the death of his wife: "How wicked it would be, if we could, to call the dead back! She said not to me but to the chaplain, 'I am at peace with God.' She smiled, but not at me. Poi si torno all' eterna fontana.""...and though she seemed to be

So far away, she smiled and looked at me,

And turned once more to the eternal Fount."

6. Letter quoted in Adele Fiske, "St. Augustine: Stages of Friendship," in Friends and Friendship in the Monastic Tradition. (Cuernavaca, Mexico: Centro Intercultural De Documentacion, 1970), 2-3. For Aelred of Rievaulx's understanding of friendship, see his classic Spiritual Friendship (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1974).

7. Regarding references to more contemporary attitudes on sexuality and passion, see C. S. Lewis, The Four Loves (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1960); Adolf Guggenbuhl-Craig, Power in the Helping Professions (New York: Paulist Press, 1981) and The Transformation of Man (New York: Paulist Press, 1967); and Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 89. For Diotima's teaching on eros, see "Symposium" in Erich Segal, The Dialogues of Plato, 263-274.

WORKS CITED

Augustine, Saint. City of God. Ed. Vernon Bourke. Garden City, NY: Image Books, 1950.

________.Confessions. Trans. by Rex Warner. New York: New American Library, 1963.

________. The Rule of St. Augustine. Trans, by Raymond Canning. Garden City, NY: Image Books, 1986.

________. Select Letters. Trans. by J. H. Baxter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

________. Soliloquies, Trans. by Rose Elizabeth Cleveland. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1910.

Brown, Peter. Augustine of Hippo: A Biography. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1950.

Chadwick. Henry. Augustine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Colleran, Joseph, trans. St. Augustine: The Greatness of the Soul and the Teacher. New York: Newman Press, 1950.

Eliot T.S. The Complete Poems and Plays, 1909-1950 San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971.

Fiske, Adele. "St. Augustine: Stages of Friendship" in Friends and Friendship in the Monastic Tradition. Cuernavaca, Mexico: Centro Intercultural De Documentacion, 1970.

Grant, Michael, trans. Cicero: On the Good Life. New York: Penguin Books, 1984.

Jung, Carl. Collected Works. Vol. 9. Princeton: University of Princeton Press, 1969.

McGuire, Brian Patrick. Friendship and Community: The Monastic Experience 350-1250. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1988.

Plato. The Dialogues of Plato. Ed. by Erich Segal. New York: Bantam Books, 1986.

| INDEX |