Conference of Major Superiors of Men, CMSM National Assembly 2003, Louisville, KY

Theme: The Image of Religious Life in Contemporary U.S. Society & Culture

Timothy Radcliffe, OP, former Master General of the Dominicans, was one of the keynote presenters at this year's CMSM Assembly. Timothy spoke to the images of religious priesthood in the context of the history of religious life in the United States and in a post-modern and highly secularized media future.

Religious Life in the World that is Coming to Be

Timothy Radcliffe, O.P.

August 7, 2003

Once, many years ago, I was preaching in my habit outside an American Air base in England, during a protest against the possession of nuclear arms. I was standing on a little box, holding forth when I heard a young boy call out in a loud and squeaky voice, 'Mummy, why is that man wearing a dress?' This rather threw my attention, but I carried on, ignoring the giggles from the crowd. The little boy shuffled up and lifted the edge of my habit and looked underneath. I then heard him say, 'Mummy, its alright. He's got trousers on underneath the skirt.'

This suggests some of the ambiguity about identity that has haunted religious life since the Second Vatican Council. Here was a young man (well, it was a long time ago!) wearing just what his contemporaries wore, a tee shirt and jeans. But over the top, he wears a thirteenth century garment, ready to be whisked off in the twinkling of an eye, especially to go out to the pub. Since the Council, many religious believed that we could only be bearers of the gospel and close to the people if we threw off the strange habits (in every sense of the word) that marked us off as strange and different. This was typified in the French worker priests, anonymously present in their factories. On the other hand, if we disappeared from sight, we might disappear entirely. And so what form of identity and visibility is best for us religious today?

One of my brethren, Herbert McCabe, had to give a lecture to the theological society in Leicester in 1990. He was in a rush, and grabbed a lecture as he ran to the train. When he arrived he spread out his notes and to his horror he saw written the dreadful words: 'Given to the Leicester Theological Society in 1989.' 'What a nightmare! How did you cope?' I asked Herbert. He replied, 'It was quite simple. I just left out the jokes. They are all that anyone ever remembers'. I find myself in a slightly similar situation. In 1996 I gave a lecture to this same Conference on the question of the identity of the religious: 'Leaving behind the usual signs of Identity'. I reread it and I have to confess that I thought that it was not bad! In a nutshell, my thesis was this: Our crisis of identity has to be placed in the context of our own society, in which everyone is suffering from a crisis of identity. In our society, people seek identity through all sorts of things that may be good and fine, which are ultimately inadequate for the children of God: status, wealth, a career, and so on. What is unique about our identity is that our vows push us beyond such identities. We have no fixed identity except as those who are on the way to the Kingdom of God. What is special about our identity is that we leave behind the usual signs of identity. We are a naked sign of the human identity, which will only be disclosed in the Kingdom.

I decided not to adopt Herbert's strategy and simply leave out the jokes, since that would have halved the length of the lecture. Instead I asked Ted to let you all have copies of the lecture, so that I could just assume that you knew my basic position, which that I still stand by. But since 1996, American society and your Church have endured two great crises that have changed the scenery somewhat. There has been the previously unimaginable event of September 11th in 2001, followed by the war in Iraq. And the Church is still undergoing the crisis which exploded last year, caused by the sexual abuse of minors by priests and religious, and the reactions of some bishops to this. So we have to look at the question of the identity and visibility of religious in this new situation: post 9/11 and post 2002.

Forgive me for being a little over simplistic, but I would suggest that both crises made visible two things: the way that power works, and our loss of dreams. Let us begin with 9/11. Until we die, all of us have been marked by the terrible images of that day. We are haunted by what we saw: people leaping from windows to their death, the second plane smashing into the tower, the terrible moment of collapse of the towers. These images have changed us. What became visible that day? It was a terrible violence that permits no dialogue. It was a brutal power the denied all communication. In fact those engines of communication, jet airlines, smashed into those hubs of economic and military communication. It was an act of dumb violence, which spoke of the absence of all speaking, an unaccountable power.

What also became visible that day was the violence of our global village. All the pain and suffering of humanity, which normally we keep far away and invisible, exploded in our face that day. The hidden violence that is implicit in the global market became visible in an instant. The Archbishop of Canterbury happened to be at a meeting just two hundred yards from the World Trade Centre, that very day. He argues that 9/11 made visible the violence that is experienced by most of the world: 'A good many who shared something of the experience of 11 September found themselves made aware that they were experiencing briefly what is the daily experience of people in other parts of the world, living under the threat of bombardment and random death.'[1] The spiral of inequality in the world is inevitably linked to a spiral of violence.

In the years that followed 9/11 something else also became visible, which is that there is only one superpower, and that its current administration feels no need to give an account of itself to the rest of the world. The collapse of communication with the United Nations, and with most countries of the European Union, the renunciation of the Kyoto Protocol, the withdrawal from international treaties suggests a power that also is unanswerable. I do not in any way wish to suggest a comparison between Al Qaeda and the Bush Administration, which would be monstrous. But it is true to say that there is a worldwide concern about what appears to be its tendency towards a power which unaccountable. So after 9/11 we all live in the shadow of powers that appear not to feel the need to give any account of themselves.

It may be forcing things a little, but there is a remote analogy with the crisis of the Church. That also is a crisis that made visible power that gives no account of itself. Luke Timothy Johnson wrote, 'The crisis in the Church caused by the sexual abuse of children by clergy will not quickly disappear, because the crisis is not about sex so much as about the abuse of power. Priests who used their position to sexually seduce or assault young people abused their power. Bishops who hid those crimes and placed priests where they could continue their predatory behaviour abused their power.’[2] The incidence of abuse, it is generally agreed, have nothing much to do with celibacy or homosexuality. It is rooted in the sexual immaturity of some priests and religious, who seek relationships in which they are able to dominate and control. It is about power! And minority of bishops who continued to reassign priests who abused to new parishes were also using a power that was unanswerable, at least downwards! Of course the relationship between Church structures and abuse is complex. The vast majority of bishops and priests cherish the dignity of the People of God. But these structures can protect a priest who is immature from the pain of growing up into relationships of equality. So, the crises of American society and of the American Catholic Church confront us with questions about the nature of power, and especially of power that gives no account of itself. It also has been for American Catholics an experience of powerlessness, of feel emasculated. The Bishops appear to feel powerless, caught between the Vatican and the media; priests feel themselves made powerless by the bishops, and the people made powerless by the priests. So it has been a time of unaccountable power and of powerlessness.

Perhaps it is not stretching things too far to suggest that these two crises also mark the end of certain dreams. Our youth was marked with dreams. Many of us can think back to Martin Luther King in 1963, 'I have a dream'. The dream was of freedom, when 'when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"' That all seems rather far away now.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Fukuyama famously wrote that history had ended. The Cold War was over and a certain political and economic system had triumphed. The violence of 9/11 was in part the protest of those who found that when history was ended they were stuck outside Paradise. The dream of global prosperity was over. The poor were just getting poorer and there was no sign that this would ever change. The Utopias of the 60s and 70s had collapsed. If the poor had lost their dreams, then so had the rich as well. After 9/11, the Bush Administration geared itself up for the long fight. The world was divided into friends and enemies; there was an axis of evil. Those who were not for us are against us. The dreams had been fading for some time. 9/11 drew a clear line under that hopeful era.

And maybe the crisis of sexual abuse draws a line after a certain time of dreaming within the Church, dreams of renewal that had been born at the Vatican Council, the time when many of us joined religious life. We had dreamed of a Church that would be filled with new vitality, new equality and dynamism. Those dreams had also been fading awhile. 2002 woke us into harsher reality. The honeymoon of Vatican Two is definitely over!

In 1996 I approached the question of our identity as religious by the via negativa: We are sign of the Kingdom through our renunciation of small and partial identities. It is the absence of wealth, career, status and even marriage that points to the ultimate human identity which will be revealed in the Kingdom. Maybe today, living in the shadow of these twin crises, we need to balance that with a via positiva. A sound theology needs both. In world marked by brutal power what visibility do we seek? What powerful presence may be ours? And in a world marked by the fading of dreams, how can we make visible God's promise to humanity?

Perhaps a good starting point for our reflections is the starting point of the Church, which is the Last Supper. For the Last Supper was a profound crisis of power and of promise. Jesus found himself at the mercy of brutal and unaccountable power. He was handed over to his enemies. He was sold by Judas and would shortly be betrayed by Peter. All initiative appeared to be out of his hands. He was a sheep handed over to slaughter, a pawn in other people's plots. And the promise appeared to be quenched. His life was going nowhere. All the excitement of those early days was finished. His life had come to a dead end. And at just this moment Jesus spoke the most powerful words of Christian history. He took bread, broke it and gave it to the disciples, saying 'This is my Body given for you'. And so with the cup. In a hopeless moment, he opened a future and made a promise.

So we should have no fear of crises. They are our specialité de la maison! We even celebrate them. Every Eucharist is the re-enactment of hope lost and renewed. Every Eucharist makes visible a crisis of power lost and regained. It shows us the extinction and renewal of promise. The end of the road becomes the beginning of the way to the Kingdom. Today we are going through a little crisis, but it is a minor one compared with the one we celebrate in the Mass. Let us discover how to live it fruitfully.

Notice the nature of Jesus' power. He is faced with brutal and blind power: the power of the imperial and the religious authorities, the power of wealth and the power of fear. He replies with an act whose power is quite different; it is that of meaning. He enacts a powerful sign, a gesture that speaks. In the face of the dumb powers that would crush him, his power is a word that opens communion. 'This is the blood of the new covenant' . It is the power of a sign and a sacrament.

The crises which American society and the American Church face are, I have suggested, crises to do with power, and the temptation of power to become dumb force. As religious, we must make visible another sort of power, which lies in the meaning of what we do or are. We need to find gestures that speak of God and the Kingdom. Cardinal Suhard once wrote that "To be a witness does not consist in engaging in propaganda nor even in stirring people up, but in being a living mystery. It means to live in such a way that one's life would make no sense of God did not exist."[3]

This has always been fundamental to religious life. The way of life of the monk and the contemplative nun speaks. Because they do not do anything, but just are there for God, then their existence is a provocative sign. The meaning of their life lies in pointing to God. If God does not exist then their life has no meaning. It is a powerful witness because of what it says of the hidden God. But the power of all religious life lies in how it speaks. Early this year I was at the General Chapter of the Franciscans, and so St Francis has been much on my mind. Francis was a man who spoke of God, through dramatic gestures. G.K. Chesterton wrote, 'The things that he said were more memorable than the things he wrote. The things he did were more imaginative than the things he said. . . From the moment when he rent his robes and flung them at his father's feet to the moment when he stretched himself in death on the bare earth in the pattern of the cross, his life was made up of these unconscious attitudes and unhesitating gestures'.[4] That is why Giotto is the perfect artist for Francis. His frescoes are like cartoons that catch the power of these gestures. The artist is at the service of their meaning.

As religious our visibility is first of all the powerful witness of lives that speak. But think of the communities of brothers and sisters living in the poorest barrios of Latin America, or running AIDS clinics in remote parts of Africa. What difference can they make? Will they halt the rise of HIV+? Yet their deepest power is like that of Jesus at the Last Supper, in the meaning of what they do. It is sacramental and symbolic.

Maybe it is the smallness of who we are and what we do that makes our signs more powerful. The morning that I prepared this lecture, the Office of Readings gave us the story of Gideon in Judges. The Lord cuts down his numbers, keeping only the three hundred who lap water. To be a sign of power of the Lord of hosts, the army had to be small and apparently ineffectual. Maybe we have been reduced and cut down, so that it can be clear that religious life makes visible a power that does not lie in big institutions, in wealth or status, but in the sacramental power of what we do and are.

This seems mad in a world where dumb power is, as from the beginning, based on the wealth and arms. It may seem even crazier in the world of the Industrial Revolution, which was based on the harnessing of force: the power of coal, steam, water, and the split atom. The power of sign, sacramental power, may seem ineffectual. It is the power of ideas, in one's head and not in the real world. Stalin famously asked how divisions did the Pope command. But we are entering a new world, that of the World Wide Web. In this new world, what principally circulate are signs and symbols, above all that symbol of everything and nothing which is money. The world of the industrial revolution is, perhaps, passing away. The main export of the USA today is so-called culture; films, icons, logos, signs. We live in what has been called 'the symbol saturated society'. [5] Advertisers know that what we consume nowadays is not products so much as cultural signs. [6] This new world will more at the service of our sort of meaning, symbolic and sacramental meaning. Just as the Franciscans grabbed Giotto to transmit the meaning of Francis' life, and the Dominicans had our homegrown Fra Angelico, so today the WWW offers a new way in which to be visible. We have largely lost the old visibility of before the Council, of big institutions with the names of our congregations splashed in ten foot high letters. We entered the anonymity of the post-Council year. Now a new visibility is possible in the www, which is that of meaning, of sign and sacrament. If we can find the right signs, then the world will hear the gospel.

The children of Abraham understand this of course. Our God created the world with a word. God spoke and it came to be. God created the world with what St Maximus the Confessor called 'the immeasurable force ofwisdom?'. The Islamic terrorists who planned September 11th understood this too. What they planned was a symbolic event. Worse even than all the loss oflife and material damage was what it said. And what it said spoke of no communication and no communion. Paradoxically it spoke ofdumb power, a word that said No.

How are we to be visible in the www? How should we be seen in the world of logos and brand names? When I was Provincial, I was a great believer in promoting the Dominican symbol of the dog with the burning torch in its mouth. We are the Domini canes, the dogs of the Lord. You can see it all over Latin America in Dominican Churches. It looks as if the dogs are smoking giant cigars. I stuck it on every Dominican product: periodicals, T shirts, buildings. Fortunately the famous sculptor Eric Gill, who as a lay Dominican, made a wonderful image of the Dominican dog that we used. It was a very well endowed dog, and had to undergo a little surgery! I read on the Zenit News Service the other day: 'The World Youth Day in Cologne has a Logo'. Let's go for brand recognition. But are we just another little company selling its goods in the global shopping mall?

I wish to suggest that just as the power that we make visible is a different sort of power from the forces that rule this world, so too 'our visibility in the world of logos is other. I suggested that 9/11 and the crisis of abuse were experienced as the ends of dreams. We lost our utopias. 9/11 drew a line under the dreams of the 60s and 70s, dreams of a future of peace and prosperity. We girded our sleeves for war. And the abuse crisis made the dreams of the post-council years seem far away. But in that deepest crisis which was the Last Supper, when all the dreams had been lost, Jesus promised the Kingdom. How in our world saturate with symbols that promise everything, can we religious be visible signs of the promise the Kingdom? What sort of sign can we be? In a nutshell, the symbols of our society promise above all two things: happiness and citizenship. And so do we, but differently. We are called to embody a different joy and a different belonging.

The signs and symbols of the www promise happiness, contentment, and the full human life. There used to be an advert in England that had the line, 'Happiness is a cigar called Hamlet'. Happiness is the beer you drink and the clothes that you wear and the car that you drive. If we are to flourish and be visible in this world, then it must be because we embody a happiness that inexplicable and provocative.

The first tiny seed of my vocation was planted in my head by an ancient and eccentric Benedictine great uncle, and that was because he was one of the most joyful people I had ever meant, provided that my mother remembered to give him a large glass of whisky at night. And if he would not go to bed, then she would leave another one at the top of the stairs, to lure him up! We cannot be preachers of the Kingdom if we are miserable. Nietzsche said that the followers of Jesus should look a little more redeemed! And even as a child I could glimpse that this joy somehow came from that crazy way of life, which was poor, chaste and obedient. .

These vows mean nothing unless they form us people who can offer a taste of joy that transcends every delight proffered on the www. It is the foretaste of the joy of the Kingdom. Blessed Raymond of Lulle, a thirteenth century Franciscan (you can see I did my homework for the OFMs), wrote, 'Lord, since you has put so much joy in my heart, stretch it out, I beg you into all my body, so that my face, and my eyes and my mouth and my hands and all my members feel this joy. King of kings, high and noble Lord, when I remember eternal life, when I contemplate it, I am overwhelmed and covered with joy. The sea is not as full of water as I am of joy.'[7]

Obedience has no sense unless it is the joy of giving your life away. One of my brethren, Jean Jacques Pérènnes, worked for 12 years in Algeria as an economist. One day he was invited by his Provincial to return to France, to teach in the University at Lyons. This plunged him into an initial gloom, and until suddenly he tasted the joy of having given his life away. As typical Frenchman he went and bought a bottle of champagne to drink to the freedom of his vow. He was happily settled into Lyons, when I phoned and I asked if he would come to Rome to be my Assistant for Apostolic Life. He asked if he think about it for a month. I suggested that maybe he could decide in a day. Another bottle of champagne! Now he is the Superior of our Arab Vicariate. He has now asked that I come and be part time with our brethren in Iraq. Guess what? More champagne!

The only possible justification for the vow of chastity is that it makes us happy. That at least was St Augustine's view [8]. He asks, 'Who can consciously embrace something that does not delight him?'[9] Someone wrote -- I forget whom -- that if Freud thought that God was all about sex, then Augustine thought that sex was all about God. Chastity is an entry to the utter and incomprehensible joy of the Father in the Son and the Son in the Father, which is the Holy. It is true that some deep pleasures take time to learn. It took me years to learn to love whisky, but I stuck at it. I am still working at chastity!

This joy was the beginning of the mission of Jesus at his baptism, when he heard the Father's delight in him. Meister Eckhart wrote that at the heart of God's life is this uncontainable laughter. 'The Father laughs at the Son and the Son laughs at the Father, and the laughter brings forth pleasure and the pleasure brings forth joy, and the joy brings forth love'.[10] We are destined to find our home in that mutual pleasure. Chastity is a mean and stifling oppression unless it is lived as the overflowing of the God's delight in all human beings. The vow of chastity should form us to take pleasure in people, the utter and overflowing delight that the Father takes in us, the joy he has in human beings in the Son. Chastity is just a way of taking pleasure in people. And one only has to glance at Francis to see a joyful love affair with poverty.

So let us all means make ourselves visible. Let us have logos; lets make a noise in the media. But the visibility that we seek is more than just another smiling face on the billboards. It is the glimpse of a joy beyond words and imagination. In a world that has lost its dreams, people may hear a voice that says even on the cross, 'Today you will be with me in Paradise.' This is a joy that makes the delights of the products of the www look thin.

But the www does not only promise happiness; its products offer us a community to which we may belong. To buy a McDonalds burger is not just to get something to eat; it is to join the communion of burger eaters throughout the world; it is to share a world. Burger says, paraphrasing Freud, 'sometimes a hamburger is just a hamburger. But in other cases, the consumption of a hamburger, especially when it takes places under the golden icon of a McDonald's restaurant, is a visible sign of the real or imagined participation in global modernity.[11] Burger King runs a Kids Club, with branches in 25 countries and four million members, more than all the religious in the world. A representative said, 'We want to capture the minds and heart of kids and keep them until they are 60 '.[12] This is a secularized version of the old Jesuit claim! To buy a pair of Nike shoes is to acquire more than something to put on your feet. It is to become a sort of person, member of a community of people. The Vice President of Nike said, 'We always describe the brand as a person. So who is that person? A person that you would like to hang out with. First and foremost, they would be funny ... So what we are doing is build up a personality.' [13]

And if you have not the money to enter the communion of the blessed, then you can buy imitation goods: fake Rolex watches, Chinese jeans with Levi labels. Every one may know that these are not the real things, but they express the desire to belong to the communion of consumption. For the poor, they are sacramental of their fantasy participation in the eschatological shopping mall. I find all this so fascinating that I find it hard to drag myself away and get back to the subject of religious life!

Religious life makes visible another sort of belonging. Our visibility is not that of another brand on the market, Dominican dogs rather than hot dogs. Our vows should form us as those who make visible another form of communion, that of the Kingdom. In my lecture in 1996, I already talked about how the vow of poverty is a renunciation of the sort of identity which consumer goods can give us. We are called to be a sign of the Kingdom by giving up the signs of status and wealth. The vow of poverty is a sign of that communion from which no one is excluded, even those who cannot afford fake designer labels, the poorest of all.

Perhaps the vow of obedience above all forms us as people whose lives point to a new way of belonging together. Indeed it is the only vow that Dominicans explicitly take, which is maybe why young OPs sometimes joked about being dispensed from the others: 'Timothy, could I be dispensed from chastity during my holidays?' Obedience for us is much more than doing what you are told. It is an acceptance that it is with these brothers and sisters that one may discover who one is and who one might become. It is the profession that one is not the master of one's own identity. This emerges through our common life.

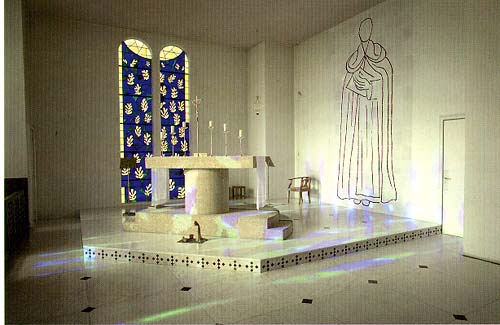

Matisse made a wonderful stain glass image of St Dominic in our chapel at Vence, in the south of France. Dominic's face is blank, of white glass. This is not because he was a colourless character, but because he was Brother Dominic. He was not so much the founder, but one of us. He created a community not to realize his will, but in which we could together discover who we are and what we may do. Incidentally, it because fraternity is so fundamental that for me the question is never: 'What is the identity of a brother in a clerical institute, like the Dominicans?' It is rather: 'What does it mean for a brother to be ordained?'

To be an obedient brother is not yet to know fully who you are. You are bound up with brethren and sisters all over the world, whom you do not yet know and yet who are flesh of your flesh and bone of your bone. The joy of being Master of the Order was that one could walk to any Dominican community in the world, from Tokyo to Buenos Aires, and know that one would discover one's brothers and sisters. We also belong to generations yet to come, who will have their say in who we are and what we may do. The young who enter today will be part of our future pilgrimage towards self-knowledge. Brethren who made profession in the States thirty or more years would never imagined that this would mean that they are brothers of people of all sorts of different ethnic and cultural groups. They did not know what they were doing. None of us do!

This is why 1 always strongly resisted the tendency to ask the brethren, prior to an election, whether they would accept to be superiors. It is not for me to say whether I think that I can perform this role. That is for my brothers to discern. They know me better than I know myself. To become a superior is not to make a career move. It is to accept the voice of one's brothers who say, 'We believe that you may fulfill this role.' To place oneself in the hands of the brethren at profession is to accept that one's identity is out of one's hands. Fraternity is an open-ended identity.

Obedience does more than commit us to an identity as religious that is beyond our imagination. It is a small sign that makes visible the unimaginable communion that is the Kingdom. When the war with Iraq loomed, members of the Dominican Leadership Conference of the United States distributed bumper stickers that said, 'We have Family in Iraq.' In the first place this referred, of course, to our Iraqi Dominican brothers and sisters. But that belonging within the Order is a sign of a wider belonging, to Iraqi Christians and Muslims, flesh of our flesh in the Kingdom. Sometimes, when Helder Camera heard that the police had taken a poor man to prison, he would ring up and say, '1 hear that you have arrested my brother'. And the police would be very apologetic. 'Your Excellency, what a terrible mistake! We did not know he was your brother. He will be released at once!' And when the Archbishop would go to the police station to collect the man, the police might say, 'But your Excellency, he does not have the same family name as you.' And Camera would reply that every poor person was his brother and sister

So the open-ended identity of the vow of obedience is a sign of that journey towards self-knowledge that we make with strangers on the way to the Kingdom. It means that we do not know who we are without the poor and the nameless and the silent. Rowan Williams wrote, 'It is not without each other that we move towards the Kingdom; so that the Christian history ought to be the story of continuing and demanding engagements with strangers, abandoning the right to decide who they are. We shall none of us know who we are without each other -- which may mean we shan't know who we are until Judgment Day.' And if obedience is more than doing what you are told, so too chastity is more than not sleeping with other people. It is nothing if it does not make visible a love that is beyond bounds, which is the life of the Kingdom. As Augustine understood so well, chastity is the liberation of desire from all the libido dominandi, the temptation to make ourselves God, and to rule and possess other people. As Sebastian Moore wrote, 'Lust, then, is not sexual passion out of control of the will, but sexual passion as a cover-story for the will to be God'. [14] In a world in which dumb and brute power has become horribly visible, then the vow of chastity should make visible desire that is liberated from all domination and mastery.

So, if religious life is to flourish, then we must be visible. People must know that we are around. But our visibility is not that of just another logo or brand name. The power of our presence lies in the meaning of what we do and are. In that sense it is sacramental, and indeed part of God's speak a word today. Most of our orders and congregations began with some dramatic gestures that spoke of the Kingdom. How may our lives speak today? For the www is ready to be a vehicle for our signs and sacraments, if we can but be brave and creative enough. And in a world that has suffered from the retreat of dreams, then the temptation to is to be seduced by the promises of the www, which speak of happiness and belonging. I believe that the vows forge us bearers of a joy and a belonging which transcend the human imagination, but which may be recognized as our deepest longing.

---------------------------

[1] Writing in the Dust: Reflections on 11th September and its aftermath. London 2002 p.62

[2] ‘Jesus and the little children’ Priest & People, March 2003 p.102

[3] Growth or Decline, Notre Dame 1951, quoted by S Hauerwas, Sanctify the Time, Edinburgh 1998 p.38

[4] St Francis of Assisi, London 1939, p.106

[5] Scott Lash and John Urry Economies of Signs and SpaceLondon 1994 p.222

[6] Tifkin 117

[7] Discourses addressed to Thalassius Quaestio 63

[8] V Bourne Joy in Augustine's Ethicsp.9

[9] De Doctrina Christiana III 16

[10] Sermon 18, in F. Pfeiffer, Aalen 1962, quoted in Murray, op.cit. p. 132

[11] ed. Peter L. Berger and Samuel P.Huntingdom Many Globalizations: Cultural Diversity in the Contemporary WorldOxford 2002 p.7

[12] Jeremy Rifkin, op. cit. p. 110

[13] 'In the vanguard of Globalization', James D. Hunter and Joshua Yates, ibid., p. 351

[14] op.cit 105