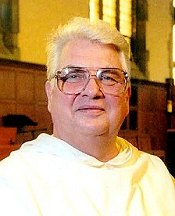

A Paper Presented by Bede Jagoe, O.P.

at the University of Salford

European Studies Research Institute

Centre for Contemporary History and Politics

International conference:

CONSTRUCTIONS OF IRISHNESS:

THE IRISH IN IRELAND, BRITAIN AND BEYOND

March 23, 2002

This paper is about a growing change in Irish identity in the USA, at least one facet of a cultural movement, a possible alteration among US citizens of Irish background in recent years.

Any realistic discussion of culture is like dipping one's toe into a flowing river. There is both the sensation of permanence and that of motion. It has occurred to me that there is a growing change in the Irish-American experience. In recent decades one's Irish identity in the USA no longer rests with one's Catholicity, but has shifted to be more identified with one's culture and heritage. I call it a change from Celtic cult to Celtic culture. Throughout this paper I will use the word Celtic in a wide sense pertaining to all that is of Irish origin, not linked to a specific pre-Christian nor Druidic connotation.

History of Ireland Emigration

To lead into this discussion let us briefly look into the history of the Irish in the USA. There were possibly 100,000 Irish Catholics in the colonies before 1700. The Penal Laws enforced by the British Parliament in 1690 brought many Irish Catholics who were forced off their land to emigrate to the West Indies and Virginia following the Cromwellian persecutions. There were more Irish Catholics in the Thirteen Colonies of 1776 than previously thought. Many were indentured servants who disappeared into places like Appalachia and since they were not well educated in their religion and since the American Catholic Church was short on clergy many became Protestants. It is worthy of note that at the time of the American Revolution there were eight Irish born, of Ulster Presbyterian origin, signatories of the Declaration of Independence; and sixteen US presidents were of Irish descent before the first Catholic president, John F. Kennedy. Interestingly , between 1827-1833 Ulster still maintained 50% of Irish emigrants, and between 1838-1841 the majority of Irish emigrants were Catholic.

Between 1779 - 1841 Ireland's population grew an incredible 172% to nearly nine million people. Then came An Gorta Mor, the Great Famine, between 1845-1850, with the blight of the Irish staple, the potato. Thousands died and thousands emigrated. English Landlords who owned 75% of the land in Ireland often came to the rescue of the starving by helping them to attain boat passage out of the country. Many Irish Catholics in the USA today trace their ancestry to those who left on 'coffin' ships to other shores.

The Great Famine

During the time of the great famine came the figure of Cardinal Paul Cullen, once Archbishop of Dublin and later Primate of Armagh. His influence upon the Irish and the Catholic Church in Ireland was enormous. Roman trained, he was described as being by temperament more Italian than Irish. He was singularly unmoved by the disaster of the famine and ascribed it as simply the work of God's providence, a calamity wrought by God to purify the Irish people. Before the famine the tenor of Irish Catholicism was a mixture of Catholic doctrine mixed with superstition and magic drawn from early Celtic mythology. Cullen took upon himself the task of re-organizing the Irish clergy, including education, and professionalizing their status in Irish society even to the point of mandating the wearing of clerical dress and the Roman collar. To the Irish Church he introduced, along side the silent, Latin Mass, 16th and 17th European Baroque devotions, such as novenas of prayer, hours of devotion before the Blessed Sacrament, processions, stations of the cross, benediction, and parish missions. Under these devotions introduced by Cullen, and probably marked by an increasing amount of spoken English rather than Gaelic, the Irish Church shed most of the remnants of Celtic spirituality and took on the 'look' of French and Italian Catholicism.

Cardinal Cullen was able to merge Irish Catholicism with nationalism. He provided the Irish with a substitute language in these prescribed devotions and offered them a new cultural heritage divorced from their ancient Celtic expressions by which they could identify and be identified.

In post famine Ireland Irish and Catholic came to be considered interchangeable.

In 1872 the celebrated Irish Dominican preacher, Fr. Tom Burke, O.P., said, "Take an Irishman, wherever he is found, all over the earth, and any casual observer will at once come to the conclusion, 'Oh, he is an Irishman, he is Catholic'. The two go together."

Emigrants after the famine were more faithfully practicing Catholics then earlier emigrants and were more likely to perceive religion and Irishness as synonymous. Between 1849 - 1878 Cardinal Cullen had utterly transformed the Irish Church, and through the agency of thousands of emigrant Irish priests, transformed the Catholic Church in America as well. Most of the early bishops in the USA were Irish born. Emigrant Irish to the US shores brought with them Cullen's devotional practices and values.

Change in Irish Identity in the USA

In recent decades the link of being Irish and being Catholic has altered. One reason is socio-religious and another factor is academic. Let us look into these aspects in some depth.

Some decades ago a sign would read. "No Irish need apply" for employment; now one can point to the affluence of Irish Catholics in the USA. As Lawrence McCaffrey, a lecturer emeritus on Irish culture, wrote in Textures of Irish America, ".the Irish journey in the United States from the unskilled working-class ghettos to the middle-class suburb is a success story in acquisition of material prosperity if not a spiritual or intellectual achievement". There is a freedom and independence of life where one is not constrained in the rural community, nor in the urban neighborhood, to attend Mass. Not being a member in the parish church or attending Mass frequently did not incur social condemnation .

At the Vatican II council in Rome in the 1960s the vernacular, singing, and participation in the liturgical celebrations were introduced as well as the possibility of attending Mass in the evening. These factors led to the disappearance of Cullen's devotional revolution. The Eucharistic celebration, the Mass, now superceded the former public devotions. The passive devotions of the earlier decades were no longer the parish ideal. Now a vital participatory liturgy with activities in parish ministries took central position. This reshaped the piety of the faithful who had once looked upon the Mass as one of many pious prayer forms. Now they found it to be a celebration where they were expected to be fully participating. There was an insistence on the Eucharistic action as the source and summit of Catholic belief. The former devotions began to disappear.

Lawrence McCaffrey points to the failure of the Catholic Church to eliminate its authoritarian character. As Irish America reached respectable, middle class, suburban status in the 1960s, symbolized by Kennedy's presidency, the Irish became integrated into the nation's cultural mainstream. As a result, loyalties to an authoritarian religious and politically "liberal" systems became contradictory. Needing connections to their ethnic heritage, Irish-Americans substituted history, literature, music and other dimensions of Irish culture for religion.

Fr. Andrew Greeley, a noted sociologist and Chicago priest, states that the Irish are more interested in their ethnic background and heritage than other national groups. After l960 and the presidential election of Kennedy a new dynamic appeared: reinterest in Ireland This would give encouragement for many Irish Americans to explore their Irish roots and for some to delve into Celtic spirituality.

In a limited survey I found two-thirds of those interviewed stated that their expression of their Irish heritage is more influential in their lives than the "faith of their fathers" i.e. their Catholicity. Those who look into Celtic spirituality find that their soul leads them to see their roots in the Druids, in their regard for nature as a meaningful expression of God's presence, finding the thin veil of the other world in their midst, and having a deep and abiding reverence for the dead as somehow still living among them. Among the Irish and Irish Americans there is an honoring of the deceased. To be seen at a wake or funeral is a sign of your respectability and your good name in the community.

Irish Studies at the University Level

An interest in Ireland must be seen in an academic light after 1980. This dynamic is connected both to the education and the affluence of Irish-Americans. Unique among Irish-Americans is the growing number of students engaged in Irish studies at university level.

Irish study programs at university level are spread over 29 States in the USA. All offer graduate and post-graduate courses leading to degrees in the humanities, usually in the English or History departments. Seven major universities have full blown programs in Irish studies, and more than 25 other universities have Irish studies programs attached to their liberal arts curricula.

The seven universities are Boston College, Notre Dame, Fordham, Catholic University in Washington D.C., New York University, St. Thomas University in St. Paul, Minnesota, and Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. Kevin O'Neill at Boston College, and Seamus Deane at Notre Dames, distinguished Irish scholars, are heading these programs. The major universities offer studies abroad for a full year, a semester, or summer sessions. These programs are linked to Queens University, University College Dublin, Coleraine, Trinity, and University College Galway.

Course-work is in literature, arts, drama, music, film, politics, economics, peace studies, folklore, history, culture, and language (Gaelic).

A number of these universities have acquired significant libraries. Each studies program produces a regular newsletter outlining weekly or monthly events. These newsletters call attention to regular conferences, colloquia, and visiting lecturers. A recent lecturer at Notre Dame was the Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney.

Each Irish studies program has its own website, and some edit their own journals of Irish studies. Notre Dame University edits Bullan, St. Thomas University produces a quarterly entitled, New Hibernian Review, and Boston College offers Eire Ireland.

One can see that this is an academic pursuit rather than religious. It is a shift from the church to the classroom. It is a movement from the parish to the university, from European devotional religion to a more Celtic spirituality and culture, from Roman back to the Irish, from personal piety to serious issues of history and society. It is a transition from Celtic cult to Celtic culture.

Catholic America, by Charles R. Morris, Chapter 2 God's Own Providential Instrument, N.Y, Times Books, 1997 ISBN 08 - 129 - 2049 - x

Emigrants and Exiles, (Ireland and the Irish Exodus to America), by Kerby A. Miller, Oxford University Press, New York, 1985, paper edition, ISBN 0-19-50394-1

History of the Irish in America, by Ann Kathleen Bradley, Chatwell Books, New York, 1996 edition, ISBN 0 - 7858- 0734 - 4

Wherever Green is Worn, (The Story of the Irish Diaspora), by Tim Pat Coogan, Palgrave Books, New York, 2000 edition, ISBN 0 - 312 - 23990 - 4

The Great Irish Famine, by Canon John O'Rourke, first published 1874, James Duffy and Co.Ltd. Dublin, 1989 edition Veritas Publications, Dublin, ISBN 1 - 85390- 049 - 0

An Age of Innocence, (Irish Culture 1930 - 1960) by Brian Fallon, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1998

New Perspectives on the Irish Diaspora edited by Charles Fanning, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, 2000, ISBN 0 - 8093 - 2343 - 5

New Hibernian Review A Quarterly Record of Irish Studies, University of St. Thomas, Center for Irish Studies, St. Paul, Minnesota

The Historical Dimension of Irish Catholicism Chapter II, The Devotional Revolution in Ireland, 1850 - 1875, by Emmet Larkin, Catholic University Press, 1997 edition

The Irish in America from Crisis magazine, by John McCarthy, March edition, 1999 New Perspectives on the Irish Diaspora

New Hibernian Review, A Quarterly Record of Irish Studies, University of St. Thomas, Center for Irish Studies, St. Paul, Minnesota

The Historical Dimension of Irish Catholicism, Chapter II The Devotional Revolution in Ireland, 1850 - 1875, by Emmet Larkin, Catholic University Press, 1997 edition

The Irish in America, from Crisis, magazine, by John P. McCarthy, March edition 1999